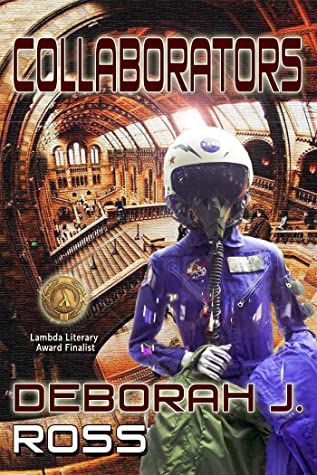

This week, I am lucky to have a fascinating guest post from Deborah Ross, whose new book, Collaborators, just released this month.

Deborah J. Ross is an award-nominated writer and editor of fantasy and science fiction, with over a dozen novels and six dozen short stories in print. Her work has earned Honorable Mention in Year’s Best SF, and nominations for Lambda Literary Award, Gaylactic Spectrum Award, the National Fantasy Federation Speculative Fiction Award for Best Author, and inclusion in the Otherwise Award List, Locus Recommended Reading, and Kirkus notable new release lists. She has served as Secretary to the Science Fiction Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA) and chaired the jury for the Philip K. Dick Award. When she’s not writing, she knits for charity, plays classical piano, and practices yoga.

Without further ado, here is Deborah!

History, Gender, and Characters

Collaborators is an occupation-and-resistance story, which at its heart is about the uses and abuses of power. In order to talk about power, I had to address the issue of gender. Gender and race inform every human interaction; from our earliest years, we are trained to respond to others as “like me” or “not like me,” and all too often treat them either kindly or harshly as a result. Rather than delve into 20th Century human gender politics (I wrote the book mostly in 1992-95) I decided to create a gender-fluid alien race in order to highlight the assumptions humans make. I wanted to create a resonance and contrast between the tensions arising from First Contact and those arising from gender expectations. What if the native race — inherently “not the same color/race/ethnicity” as humans — did not divide themselves into male and female? How would that work – biologically? romantically? socially? politically? How would it affect the division of labor? child-rearing? How many ways would Terrans misinterpret a race for whom every other age-appropriate person is a potential lover? Or, in a life-paired couple, each partner equally likely to engender or gestate a child? Maybe by the time we achieve interstellar space flight, we’ll have evolved beyond sexism and racism, not to mention homophobia and religious intolerance. One can only hope.

For my alien race in Collaborators, I also wanted sexuality to be important. I decided that young adults would be androgynous in appearance and highly sexual. Sex would be something they’d enjoy often and enthusiastically with their age-mates. However, the intense intimacy created by sex exclusively with the same person would lead to a cascade of emotional and physiological effects resulting in a permanent, lifelong pairing. The pairing, a biological bond obvious to everyone around the couple, would lead to polarization with accompanying mood swings, aggression, inability to focus. Each partner would appear more “female” or “male,” which would inevitably set up occasions for misunderstanding with Terrans, who think and react in terms of those divisions. The natives, on the other hand, would wonder how people who are permanently polarized can get any work done, and react to Terran women as if they were all pregnant, and therefore to be protected at all costs because their own birth rate is low.

Just as we’ve instituted the canonical talk about the birds and the bees, or sex ed in schools, so the natives would have traditions of preparing their young people, trying to ensure that pairing does not have disastrous political or inter-clan consequences. We know how badly that works in humans, so it’s likely to be equally ineffective with native teenagers, too.

The central inspiration for Collaborators – that individuals respond in a variety of complex and contradictory ways to a situation of occupation and resistance – immediately suggested many types of characters: the rebel, the idealist, the opportunist, the political player, the merchant willing to sell to anyone if the profit is high enough, sadist who exploits the powerlessness of others for his own gratification, the ambitious person who doesn’t care who his allies are, the negotiator, the peace-maker, the patriot.

I lived the better part of 1991 in Lyons, France, and I was repeatedly struck by how history permeated every aspect. Some buildings showed damage from cannon balls during the French Revolution. Plaques marked places where citizens were executed by the Nazis or Jewish families were deported. After visiting the tiny Musée de la Résistance, I became interested in how many varied ways the French responded to the German occupation. Some protested from the very beginning for religious or ethical reasons, but others went along, whether from fear or apathy or entrenched anti-Semitism, or simply because the war did not affect them personally. Yet others sought to exploit the situation for personal power or financial gain. Some became active only when their own personal lives were affected.

One of the first characters to speak to me arose from an unexpected source. I never knew either of my paternal grandparents, for both had perished in the lawlessness and pogroms in the Ukraine shortly after the first World War. My father told me about how his mother ran a bookstore that was the center of intellectual (and revolutionary!) thought in their village, how when that village was destroyed, she kept her two children alive as they wandered the countryside for two years, going from one cousin’s house to another but never staying very long. He spoke of her courage, her idealism, and her unfailing love. Some piece of her, or her-as-remembered, stayed with me, and I wondered if I could create a character with that strength and devotion to her children. I began to write about Hayke, who opens the book as he lies in a field with his two children, gazing up at the stars and wondering what these star-people might be like. Hayke had other ideas about what his life was like besides merely following in my grandmother’s footsteps, and everything changed once it became clear to me that the alien race were gender-fluid. Hayke, like my grandmother, was a widow (using the term generically to include both sexes), and one of his children was born of his own body, but the other of his dead spouse’s, and he told me he felt an especial tenderness for the latter child.

Even though the ground action takes place in an area roughly the size of Western Europe and most of the characters live or come from the central nation, Chacarre, I didn’t want all the national territories to be the same. I wanted differences in language, dress, attitudes toward authority, etc., between Chacarre and its rival, Erlind, and also within Chacarre itself. Every once in a while, a new character would surprise me, like Na-chee-nal with his “barbarian” vigor and his smelly woolen vest, or Lexis, the dangerously repressed academic poet.

The Terrans presented a different challenge because they were more homogeneous than the natives. They inhabit a single spacecraft and although there is a natural division between crew and scientific personnel, for the most part their goals are shared and their hierarchies are well-defined. Left unchecked, that’s a recipe for boring, so I added some friction, a few divergent motives, a highly stressed environment . . . and into this walked Dr. Vera Eisenstein, eccentric genius. Most of the inspiration for her character came from the women engineers and physicists I’d gotten to know (thank you, Society of Women Engineers!) with a touch of Dr. Richard Feynmann thrown in. She doesn’t play by anyone’s rules, she cares far more about science than diplomacy, she’s simply too good at what she does to disregard, and her mind never stays still. I had a ball cooping her up in the infirmary and watching what kind of trouble she’d get into, but I didn’t realize at first that she would become a pivotal character, one capable of acting for the greatest good despite the depth of her loss. I’d been thinking about her passion in terms of science, not in terms of her capacity for love nor in terms of her ruthless commitment to understanding everything she sees around her, whether it is a problem in laser spectroscopy or alien psychology or the nature of her own grief. In the end, that dedication to truth, inner and outward, made her the ideal person to reach across the increasingly blood-drenched rift and find a mutual, nonviolent path forward for both the Terrans and the natives whose lives have become entangled in theirs.

Collaborators Order Links

Amazon (ebook and trade paperback) https://www.amazon.com/Collaborators-Deborah-J-Ross-ebook/dp/B08747XP15/ref=sr_1_1?dchild=1&keywords=deborah+j+ross+collaborators&qid=1597367139&sr=8-1

B & N (ebook, trade paperback, and hardcover/laminated cover) https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/collaborators-deborah-j-ross/1136878756?ean=9781538013151

Kobo https://www.kobo.com/us/en/ebook/collaborators-10

Ingram:

Trade paperback: 9781952589003

Hardcover/dust jacket: 9781952589027