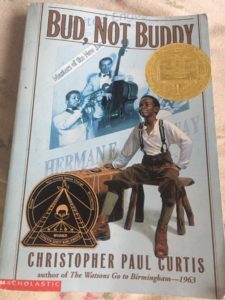

When I sat down to read Bud, Not Buddy, I thought for sure that my takeaway from this book would be all about voice. After all, Bud’s voice is soooo strong. His voice is funny and distinct and part of what makes this book so memorable. But even more important than voice, to me, was the way Christopher Paul Curtis was able to place himself so believably in the mind of a child.

As children’s book writers, it’s our job to place ourselves in the minds of children. It’s what we attempt to do each and every time we sit down to write. But too often, I think, we tell the stories in our books (at least in our early drafts) through a child’s point of view that is filtered through the brain of an adult. What we need to do as writers is sit down and really remember what it feels like to be six, eight, ten, and twelve years old. To remember the emotions, the joy, the fear, the confusion, the powerlessness, the body sensations. In the early pages of Bud, Not Buddy, Bud thinks: “It’s at six that grown folks don’t think you’re a cute little kid anymore, they talk to you and expect that you understand everything they mean….Six is a bad time too ‘cause that’s when some real scary things start to happen to your body, it’s around then that your teeth start coming-a-loose in your mouth…it shakes you up a whole lot more than grown folks think it does when perfectly good parts of your body commence to loosening up and falling off of you. Unless you’re stupid as a lamppost you’ve got to wonder what’s next, your arm? Your leg? Your neck?” (4-5)

Through each and every moment of this book, Curtis stays firmly in the point of view of a child. This leads to misunderstandings and humor throughout the book, when often the reader suspects a few things Bud does not (for example, that the dark item in the shed is not a vampire bat….).

Some writers may find it difficult to stay so closely inside the mind of a child. In the workshops I teach, I often see emerging writers struggle with point of view, often switching point of view or shifting into the point of view of an adult character when they are struggling to get some piece of information across. But I see this constrained child point of view as an opportunity, not a limitation. It is an opportunity to really FEEL what your character is feeling, to experience that character’s emotions. When your character is afraid, what does it feel like in his or her body? Are her shoulders tense? Stomach tight? Being true to your character’s limited point of view is going to create a much stronger connection between reader and protagonist than if you hop around. And staying firmly inside the head of your child character is going to make that character feel much more real to readers than if the child character thinks, speaks, and behaves in a way we suspect is a bit “adult-like.”

An exercise:

Sit down with a pen and paper and think about a time between the ages of eight and twelve. Who were your best friends? How did you feel about your parents? What were you afraid of? What were your favorite foods? Who were the kids in your class at school? What did your bedroom look like? What secrets did you have? Did you have any special objects, or belongings, that were important to you (like the items in Bud’s suitcase)? How much freedom did you have to go places on your own? What was your favorite activity to do with friends? Did you have any hobbies?

Try to place yourself back in the point of view of your younger self. This is a good exercise to repeat time and time again to remind ourselves what it feels like to be a child, which will in turn help us write better books for children.

Next Up: Island of the Blue Dolphins by Scott O’Dell!

xoxo,

Tara