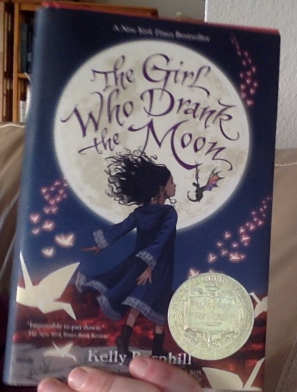

It took me much longer to read and respond to this book than I thought it would! It has nothing to do with the quality of the book – it’s fabulous – but I was a bit of a slow reader because I was also preparing for the beginning of the semester, finishing up round two of my edits on UNWRITTEN, and brainstorming/outlining a new project I am working on. Plus the book is nearly 400 pages, quite a bit longer than most of the middle grade published today. Which actually brings me to my main topic: what I learned from this book.

Do not be afraid to break the rules!!!!

By its very length alone, this book starts breaking rules. Most middle grade is around 45,000 words. Fantasy middle grade can go as high as 65,000 words because of the world-building involved, but this one clocks in at over 80,000.

The book doesn’t just break the size rules, though. Some of the main things children’s writers are told over and over are:

1. Children don’t want to read about adults. Stick to a child’s point of view.

2. Child protagonists must solve their own problems. Get the adult characters out of the way.

This book does neither of these things. For much of the book, we are in the point of view of adult characters. Luna, our protagonist, begins the book as a baby, and so we see her from the point of view of others:

Xan, a witch

Gherland, the grand elder

Antain, who starts as a boy but grows up and is an adult for much of the book

As the novel continues, we also enter the point of view of:

The madwoman

Sister Ignatia

Glerk, a bog monster

Other than the brief period where Antain is a child, Luna is the only child point of view in the book. For about a third of the book, she is younger than the intended audience (another “rule” – kids don’t want to read about children younger than themselves). And in the end (though I don’t want to give anything away), she doesn’t solve the plot’s main problem on her own: she does it with help (and instruction) from adults.

How does Barnhill get away with breaking so many rules? Why does the book work so well?

I think as children’s writers, it can be easy to get caught up in “the rules.” Though there are good reasons for these “rules,” it is also important to know when to break them. The story’s demands must always take precedence over any rules, and an author must make choices based on what is best for the story.

For example, if everyone followed the “rule” about not writing stories about adults, then we wouldn’t have characters like:

Mrs. Piggle Wiggle

Frog and Toad

Amelia Bedelia

Kids LOVE these stories about adults. The key here is that these characters are very “child-like” – their concerns, characters, and story problems are very similar to ones children face. For example, Amelia Bedelia, who has the best intentions but never seems to quite follow directions the way she is supposed to, has a problem that many (if not all) children can relate to: misunderstanding directions/doing things wrong. (Also, she is silly! Kids love the humor of these books!) Are kids going to want to read stories about adults going to a nine-to-five job and fighting traffic and stressing about the mortgage? No! But they can relate to adult characters like Frog and Toad. Or Xan, Gherland, and Glerk, who in Barnhill’s novel function in much the same way adults do in fairy tales. They represent fantasy and magic, as well as good and evil. Gail Gauthier gives an interesting discussion of adult characters in children’s books here.

Barnhill’s entire novel reads very much like a fairy tale. It is filled with magic, myth, and fantastical creatures. She is not afraid to tackle tough subjects like the nature of evil, forgiveness, and mortality.

Luna, the protagonist, does not solve the final problem on her own, but in this book, the ending feels just right. Barnhill has created multiple plotlines, with multiple points of view, and she has crafted an ending so that all of these separate plotlines converge and come together in the end to form one satisfying conclusion. Barnhill’s ending feels just “right” — I suspect it is much more satisfying than if she had imposed a different ending on the story, one that made sure Luna did everything on her own. It feels right that all of these characters we have been following throughout the story should work together in the end. Barnhill did not sacrifice the demands of the story to arbitrary rules.

(I could write an entire essay on how brilliant Barnhill’s ending is, by the way. It takes real skill to make so many plotlines come so perfectly together the way she did.)

This just barely skims the surface of all the lessons I could glean from this book, but as I was reading, it was the lesson that popped out at me over and over again. Break rules!

Are you looking for a challenge? Here’s an exercise:

Create an adult character in the vein of Amelia Bedelia, Mrs. Piggle Wiggle, Xan, Glerk, or Frog and Toad, one you think kids will be willing to follow. What will make this character appeal to kids? Why are their interests and conflicts ones that will resonate with kids?

Next up on my list: Bud, Not Buddy by Christopher Paul Curtis